fromwww.aljazeera.com

2 hours agoCitizens of Nowhere: What It Means to Be Stateless in the US

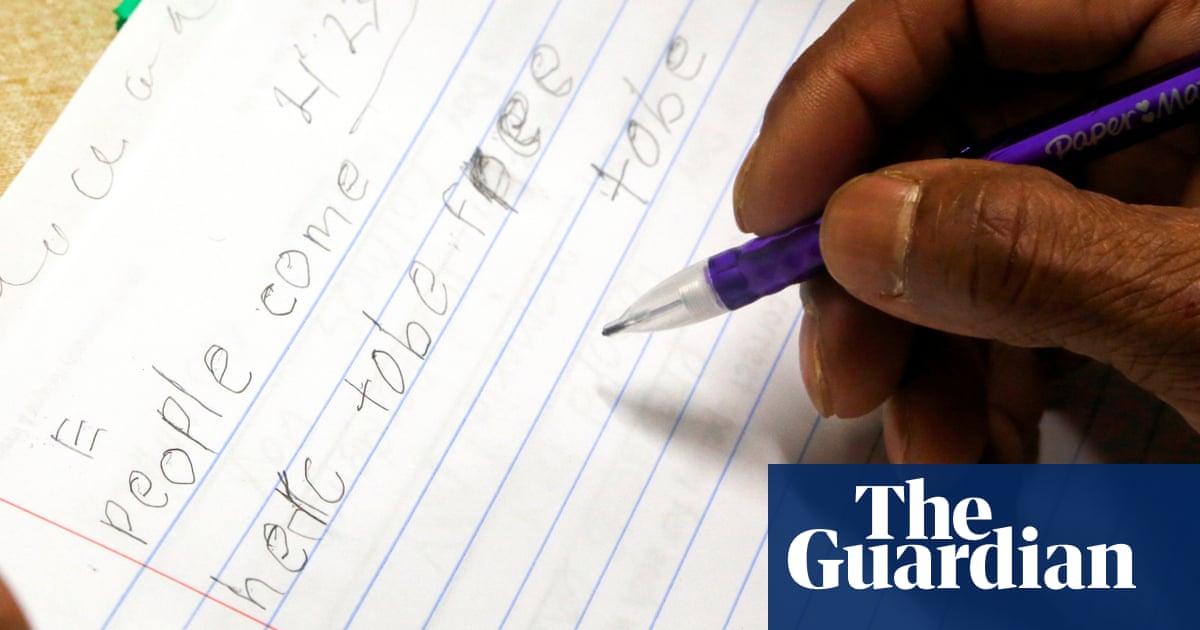

Citizens of Nowhere is a documentary short about stateless people in the United States individuals who, through circumstance or legal technicality, belong to no nation. Without passports, citizenship or legal recognition, they live in a state of uncertainty. From finding work and accessing education, to simply existing within a system that does not officially recognise them, stateless people face endless bureaucratic barriers.

Film