#thwaites-glacier

#thwaites-glacier

[ follow ]

#sea-level-rise #antarctica #ocean-warming #glacial-earthquakes #antarctic-research #glacial-melting

fromThe Atlantic

4 days agoA $40 Billion Idea to Keep One Glacier From Flooding the Earth

On Thwaites itself, part of the team will try today to drop a fiber-optic cable through a 3,200-foot borehole in the ice, near the glacier's grounding line, where the ocean is eating away at it from below. Sometime in the next week, another part of the team, working from the South Korean icebreaker RV Araon, aims to drop another cable, which a robot will traverse once a day, down to a rocky moraine in the Amundsen Sea.

Science

fromMail Online

6 days agoWhat could go wrong? Experts DRILL into Antarctica's Doomsday Glacier

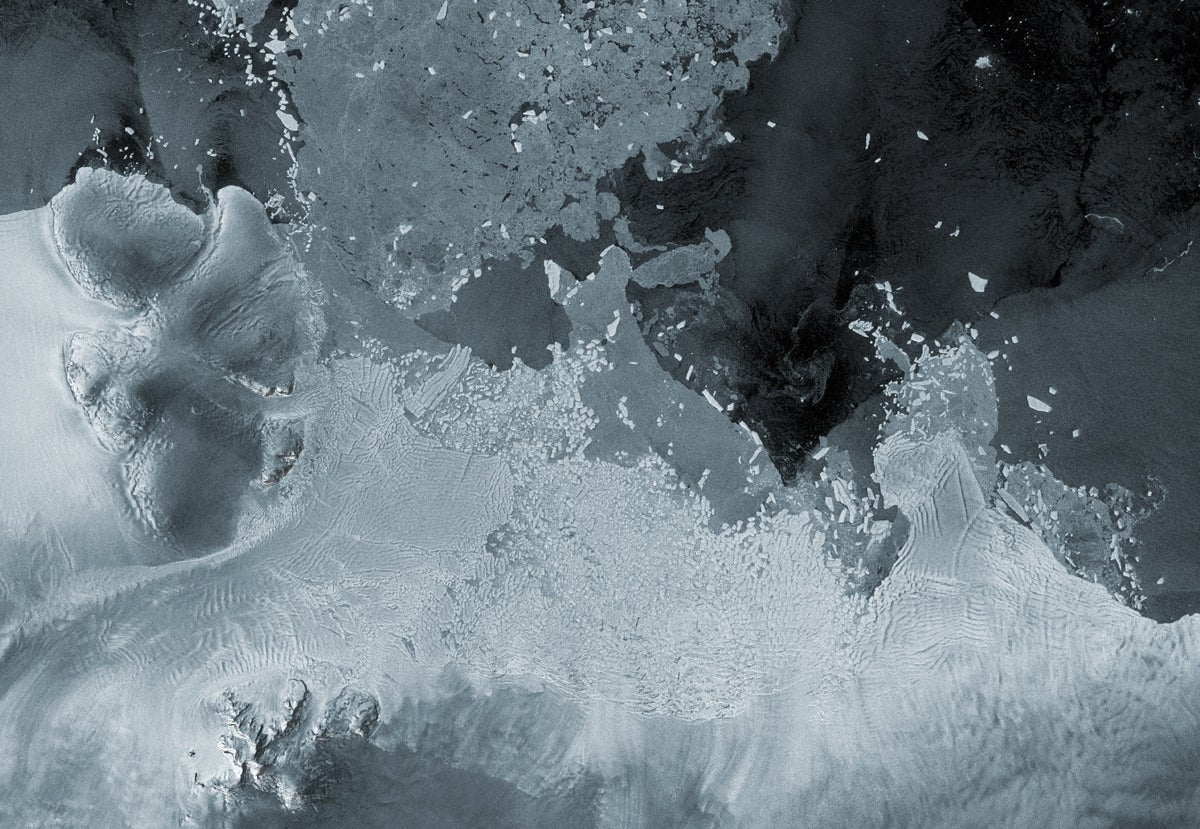

Measuring around the same size as Great Britain, this huge mass of ice in West Antarctica is one of the largest and fastest changing glaciers in the world. Worryingly, research has shown that if it collapses, the glacier will cause global sea levels to rise by a whopping 2.1ft (65cm) - plunging entire communities underwater. For this reason, it has been nicknamed the 'Doomsday Glacier'.

Science

fromFuturism

1 week agoScientists Scramble to Set Up Outpost on Rapidly Melting Glacier

During a rare break in the weather, the NYT says helicopters airlifted the researchers and their equipment 19 miles to their planned outpost site on top of the glacier. The two helicopters involved flew a dozen total loads of cargo from the icebreaker ship to the camp site, while glacial scientists and engineers erected a small tent city, complete with bathrooms, generators, and a mess hall.

Environment

fromFuturism

1 month agoDoomsday Glacier Approaching Catastrophic Collapse

Scientists have watched in horror as its retreat has accelerated significantly. Now, as detailed in a study published by the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration (ITGC) and spotted by Wired, large cracks forming in the ice shelf are continuing to weaken its structural integrity. Doomsday has never been closer. If it were to collapse under its own weight, scientists suggest it could ultimately trigger up to 11 feet of global sea level rise, meaning certain devastation for tens of millions of people.

Environment

fromMail Online

2 months agoAntarctica's 'Doomsday Glacier' is on the verge of COLLAPSING

Study author Mattia Poinelli at the University of California, Irvine, said the vortexes 'look exactly like a storm' and are 'strongly energetic'. 'There is a very vertical and turbulent motion that happens near the surface,' Dr Poinelli told climate organisation Grist. 'In the future, where there is going to be more warm water, more melting, we're going to probably see more of these effects in different areas of Antarctica.'

Environment

[ Load more ]